Search for:

The Hiring Line Initiative empowers voters to achieve an economically just immigration policy. A properly regulated system will restore opportunities for left-behind Americans. There is a long history of legislation siding with employers’ preferences for foreign labor over Black Americans.

We have the receipts.

Jump to

Before the War

The first wave of mass immigration after 1820 drove free Black workers from their fragile economic holds in the North. Employers preferred immigrant workers over Freedmen. And immigrant unions worked to drive Black workers off job sites.

The Great Wave

In the aftermath of the Civil War, free Black Americans briefly found new opportunities in the expanding industrial North. Black incomes grew to more than 70 percent higher than in the South in just a few years. The racial wage gap improved by nearly half over the next decade as more Black Americans moved north. But starting in the 1880s, what came to be known as the “Great Wave” of immigration once again afforded Northern industrialists the luxury of not hiring Black workers.

The Great Wave of immigration between 1880-1924 reduced the economic opportunities for Black Americans in the North. As they had before the war, immigrant unions viewed free Blacks and emancipated slaves as labor competition. Unions expelled their own white members if they were caught working on a job site with Black workers. Frederick Douglass’ own son, Lewis, who had served in the famed 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, was barred from union membership and then protested as a scab for taking a non-union job.

The record levels of immigration also changed the political balance against Reconstruction. Most new immigrants settled in northern cities and joined the anti-Reconstruction Democratic Party. Thus, the Great Wave diminished both the economic opportunity and political power of Black Americans. By 1876, the emerging Democratic majority had negotiated the withdrawal of federal troops from the South.

Mass immigration was enough to keep most Black Americans trapped in the unreconstructed South for another half century.

The lasting symbol of the Great Wave, the Statue of Liberty, was conceived as a celebration of the liberation of American slaves. It was mere coincidence that the ships carrying new immigrants passed by the pedestal with the broken shackles around the statue’s feet. Ironically, the Great Wave ensured that Black Americans would remain economically shackled to the South decades after emancipation.

The Great Migration

The “Great Migration” of American Blacks moving from the South to the North and West began when mass immigration came to an abrupt halt at the outbreak of the first world war. Bigotry was no longer a luxury Northern industrialists could afford. Twenty years after Booker T. Washington called on American employers to “cast down your bucket where you are,” industry leaders sent labor scouts south to recruit Black Americans.

Over the course of the war, 1915-19, half a million Black southerners migrated to the industrial belt from New York to Chicago.

Mass immigration resumed after the war, but Black leaders like A. Philip Randolph successfully lobbied to permanently lower immigration to more moderate levels. President Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924 into law and the Great Migration took off. When the Great Migration began, 90 percent of Black Americans were living in the South. By the 1970s, nearly half were in the North and West.

The Great Leveling

In addition to the Great Migration, the moderate levels of immigration over the next four decades contributed to the “Great Leveling,” when America truly became a middle class nation. Between 1940-1980:

The Broken Promise of 1965

Just as civil rights leaders like Booker T. Washington and A. Philip Randolph had believed, Black economic power lead to Black political power. But just as Congress was tearing down barriers to social equality during the Civil Rights Movement, it rebuilt an old barrier to economic equality by restarting mass immigration.

The positive economic trends for Black Americans stalled in the 1970s. Today, after 50 years of the biggest wave of immigration in history, almost all of the gains of the Great Leveling have been lost. By 2018, 42 percent of all Black men (25-34) earned less than the $25,100 necessary to keep a family of four above the poverty line.

The Wages of Indifference

The legislators who restarted mass immigration in 1965 claimed that they did so by accident. But since then, multiple Congresses and administrations have ignored the recommendations of every blue-ribbon federal commission to reverse the mistake. Instead, lawmakers have doubled down on mass immigration.

In the 1980s, Congress gutted workplace enforcement provisions from a bill that granted amnesty to illegal workers, and de-facto amnesty to illegal employers.

In the 1990s, Congress responded to what the Department of Labor called an “unprecedented opportunity” for employers to offer better job prospects to Black workers with the largest immigration increase in U.S. history.

In the 2000s, Washington, D.C. drove African-American workers displaced by Hurricane Katrina off the recovery job sites by suspending immigration enforcement.

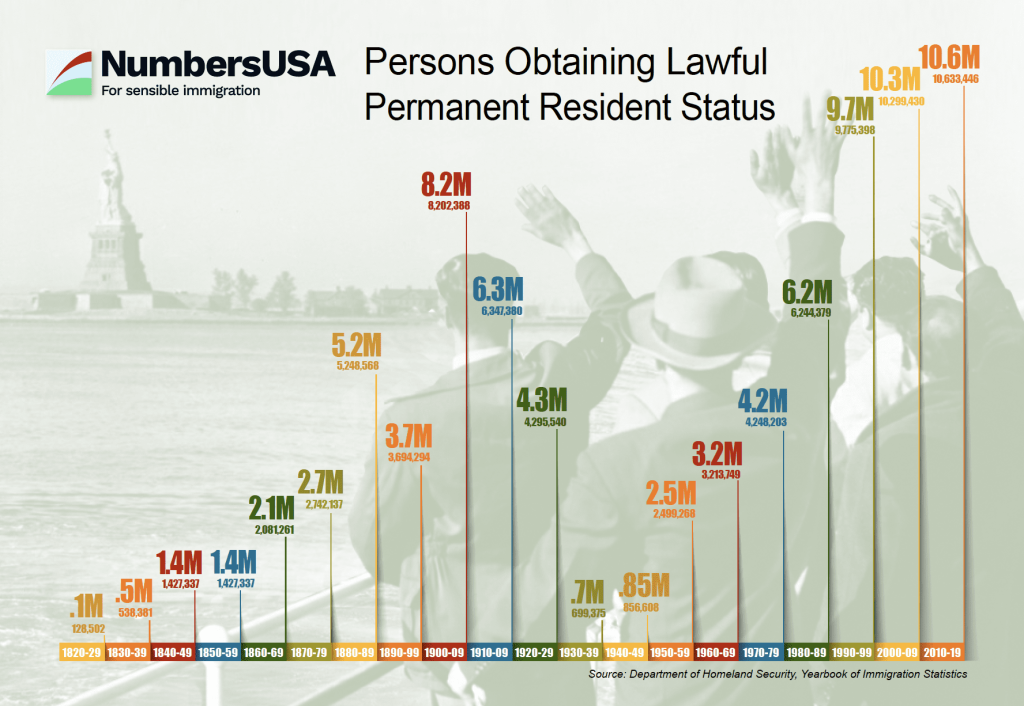

In the 2010s, the poverty rate for Black Americans was 80% higher than the national average. One out of three Black children lived in poverty while one out of every two Black working-age adults without college degrees were not working. Congress remained indifferent. More permanent work permits were issued to new immigrants in that decade than any other in history.

In the 2020s, illegal immigration has grown to more than twice the level of legal immigration, and Black communities are once again being displaced.

Here’s more about what we do:

We provide civic engagement through education and easy-to-use tools for legislative outreach among grassroots activists and concerned organizational leaders: research, factsheets, live events, speaking engagements, and alliance building. Be a change agent. Actions here!

Looking for a book? Pick up Back of the Hiring Line.

Roy Beck tells the 200-year history of immigration surges, employer bias, and depression of Black wealth. Populated with the likes of Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois, A. Philip Randolph, Barbara Jordan and other African American leaders, the book pulls multiple histories into one place, and saves the receipts.

Looking for a speaker? Contact Andre Barnes, HBCU Engagement Director. Andre’s ongoing relationships with our country’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities ensures we are engaging with tomorrow’s leaders and innovative thinkers.

Ask Andre about what he or other members of the Hiring Line team can bring to your group or event.

Looking for help in your community? NumbersUSA’s Hiring Line team works with local groups to give them a stronger voice in Washington D.C. while further empowering them close to home to achieve a sensible immigration policy.

Every state is a border state. Communities facing the most difficult downstream impacts of an irresponsible policy are frequently among the most disenfranchised, historically and today.

Jump to