February 21, 2024 – Today is Barbara Jordan’s birthday. She would have been 88 years old. Tragically, she died in 1996, just before Congress voted on the immigration recommendations she developed over the last years of her life.

If you don’t know much about Barbara Jordan, you should look her up. She regularly appears on lists of great American orators. Jordan’s life story is full of “firsts,” including the first Southern Black woman to be elected to the House of Representatives, and the first woman to deliver the keynote address at the Democratic National Convention.

If you are concerned at all with immigration policy, you must learn about Barbara Jordan and the last act of her illustrious life and career. Her work as chair of the last bi-partisan commission to study immigration is essential to understanding where we’ve been; and necessary for us to see where we need to go.

Related: U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform: Guiding Principles and Recommendations

Growing up during the Great Migration

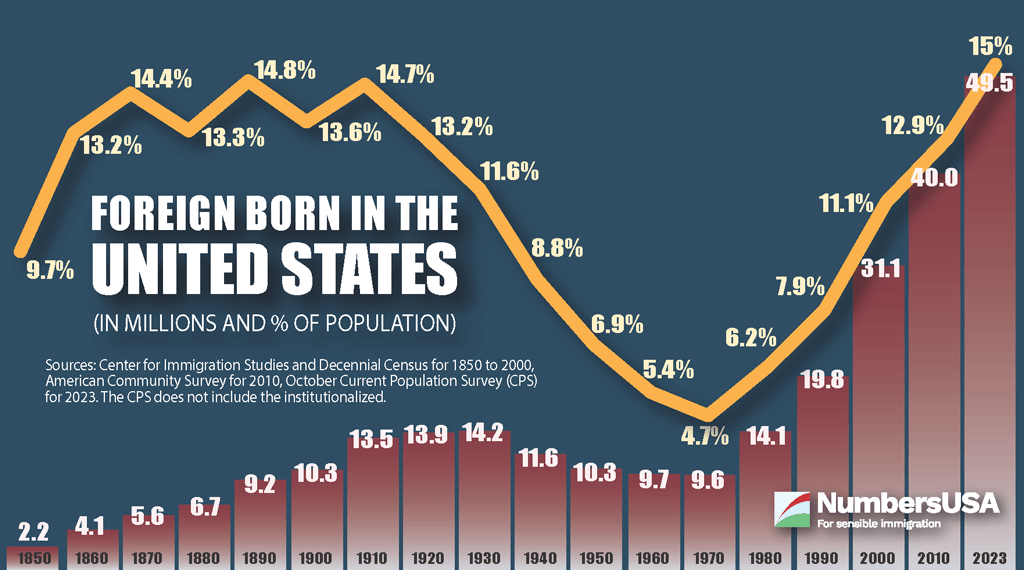

Jordan was born in 1936, twelve years after the Immigration Act of 1924 was signed into law (one hundred years ago this May). That bill permanently ended The Great Wave of European migration (after the Great War had temporarily halted it in 1917). The slowdown of ships from Europe forced Northern industrialists to do the unthinkable: they sent recruiters to the far corners of the deep South and recruited the descendants of slaves and American Freedmen. The result was The Great Migration of Black Americans into the North and West. White workers’ income went up two hundred and fifty percent. Black workers’ income went up four hundred percent. W.E.B. DuBois called the immigration slowdown “the economic salvation of American black labor.” DuBois’ declaration was echoed by Black journals and newspapers.

Jordan grew up during segregation and other forms of institutionalized racism. She also grew up during The Great Leveling and the rise of the Black middle class whose economic gains led to new political power. In the year before Jordan was elected to the Texas State Senate (another first), Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1965. Four decades of economic empowerment had finally led to the dismantling of institutional barriers to social equality.

Righting an old wrong; creating a new one

As Jordan was on the cusp of beginning her political career in the Texas Senate, legislators in Washington, D.C. were about to make a mistake that Jordan would spend the coda of her political career trying to clean up. In the spirit of the civil rights movement, and to honor the slain President Kennedy, Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. In doing so, they righted an old wrong, and created a new one.

Multiple administrations and Congresses had criticized one aspect of the immigration system created by the 1924 law: national-origin quotas made it virtually impossible for anyone outside of Europe to immigrate to the United States. The 1924 Act drastically reduced immigration from Europe, but it effectively banned immigration from other parts of the world, regardless of an individual’s merit. If the fundamental questions of immigration policy are “how many” and “which ones,” the 1924 Act was right on the former, and wrong on the latter.

“Everywhere else in our national life, we have eliminated discrimination based on national origins,” Senator Ted Kennedy said, “Yet this system is still the foundation of our immigration law.”

Kennedy and his fellow reformers vowed to leave the successful “how many” part of the 1924 Act in place. They promised a system that would admit 265,000 immigrants per year. Their aim was only to recalibrate the “which ones” part. The new system, they promised, would be less discriminatory. A nuclear physicist, for instance, wouldn’t be denied just because he or she came from the “wrong” part of the world.

In the end, the bill changed both the “which ones” and the “how many.” The discriminatory quotas were abolished, but immigration numbers almost immediately doubled. Decades of declining inequality, an expanding middle class, and shrinking racial wealth gaps were halted and reversed. Inadvertently, it seems, Congress created new economic barriers to equality within a month of passing landmark civil rights legislation.

The 1965 Act was the photo negative of the 1924 bill. The legislation got the “which ones” right and the “how many” wrong. The challenge for policy makers today is to get both parts right. Nobody in the last half century has provided a clearer roadmap to achieving that sensible balance than Barbara Charline Jordan.

Credibility

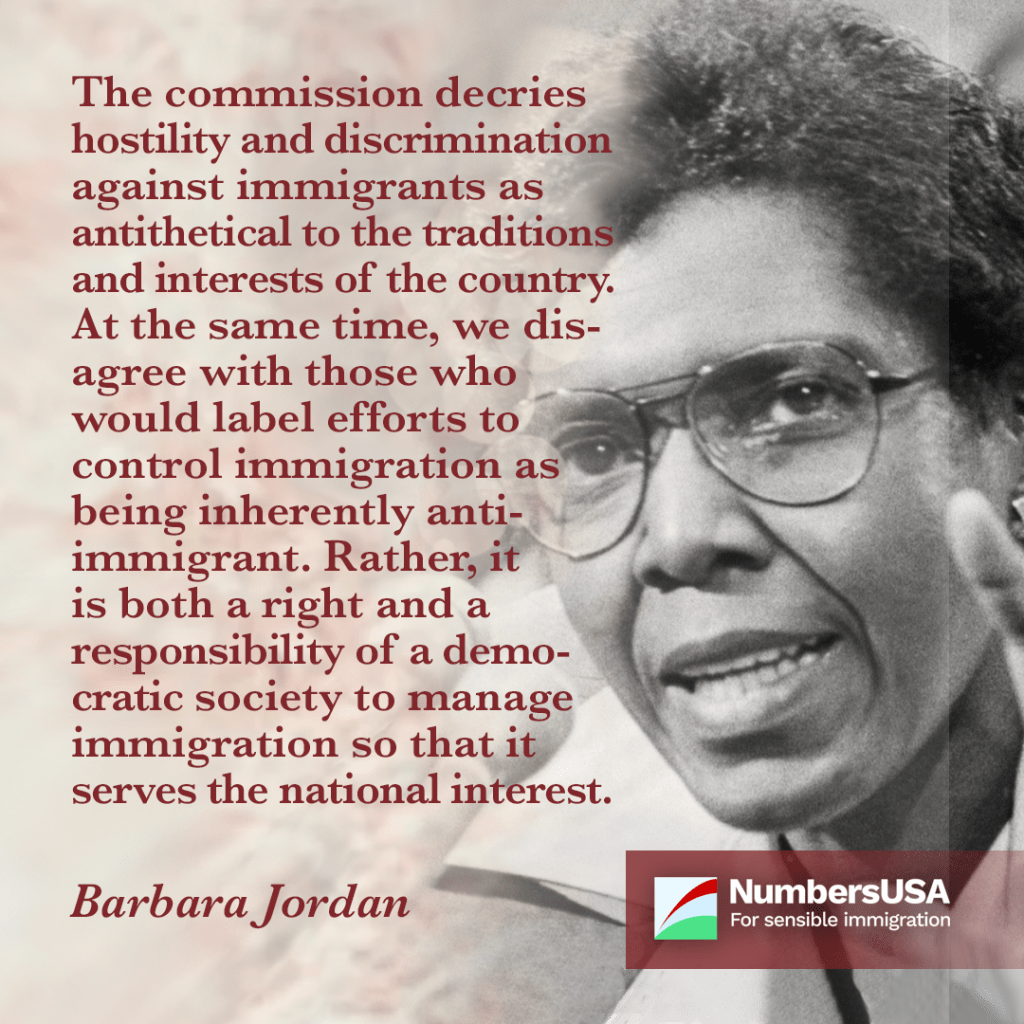

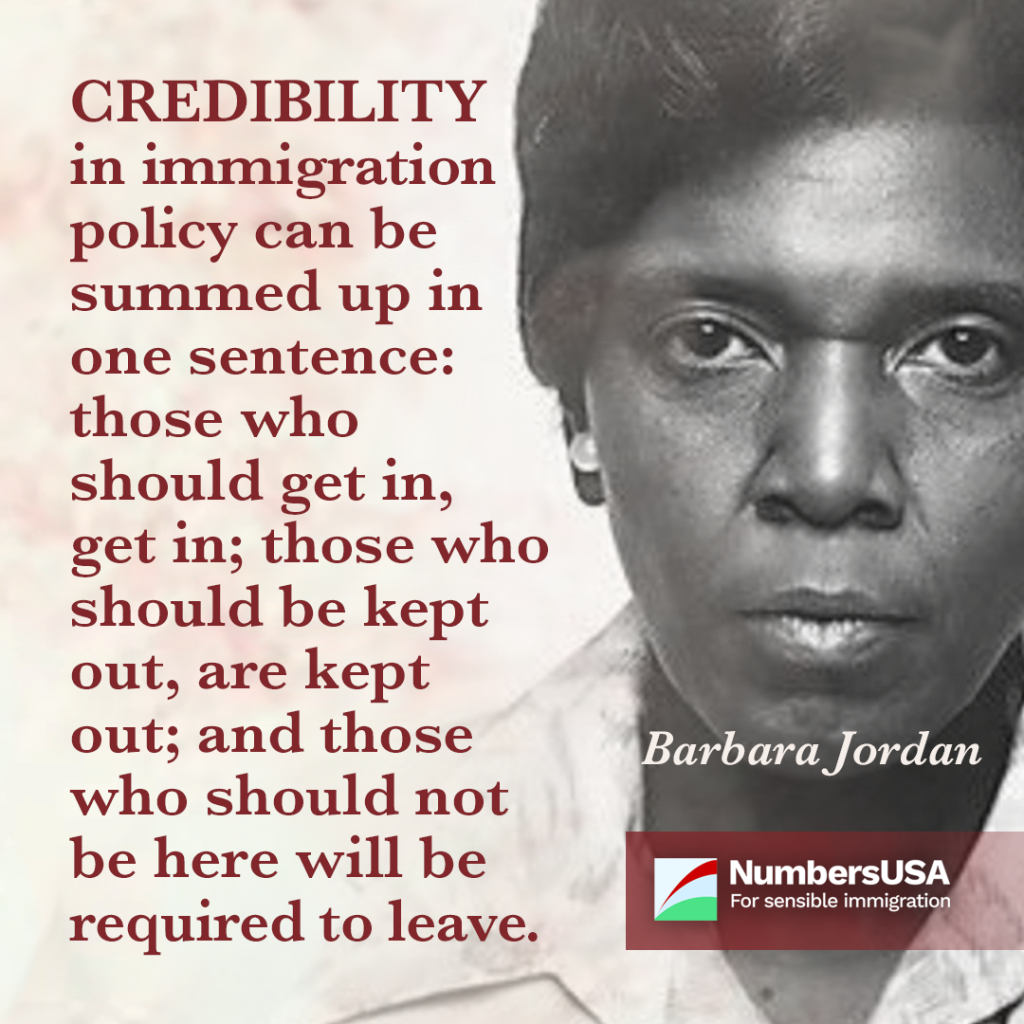

Jordan believed in welcoming immigrants into the American community. A Civil Rights icon in her own right, Jordan loathed discrimination, bigotry, and name-calling. She was adamant that immigration policy should serve the members of the national community, with special attention paid to vulnerable Americans. She made no apology for setting limits, and she advocated for enforcement that would give those limits credibility. Her own credibility was unimpeachable.

Related: Barbara Jordan’s Vision of Immigration Reform

Ironically, Jordan did not focus on immigration policy during her time in Congress. She initially refused her appointment to chair the immigration commission citing health issues and a lack of background in the subject. But immigration was roiling American politics at the time and America needed someone all sides respected to lead the commission. Jordan was a brilliant choice, but her task would not be easy. Americans were losing faith in the immigration system itself.

More broken promises

Jordan and her commission would be tackling the downstream effects of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. The bill had failed to deliver the promised tight labor markets for American workers. In addition to the increases in legal immigration, employers were hiring illegal workers instead of Americans as well. Jordan had left politics by the time a 1986 bill attempted a compromise solution by issuing amnesty to 3 million illegal workers in return for promised workplace enforcement. The enforcement never materialized; another betrayal.

Meanwhile, business lobbies had become reaccustomed to ample access to a global labor market, and were lobbying for more. A year after the 1986 amnesty, the Department of Labor warned of a looming worker shortage unless America embraced an “unprecedented opportunity” to “provide better job prospects for historically disadvantaged groups and to invest more heavily in their education and training.”

Congress found another solution. They passed the largest immigration increase in U.S. history. The Immigration Act of 1990 was signed into law just before a recession struck. Immigration soared to over one million per year, where it has remained to this day. The number of leaders concerned about the broken promise of 1965 dwindled.

Credible, coherent, and in the national interest – the Jordan Commission

Champions of American workers did get one concession from the 1990 bill: a mandate for a bipartisan commission to “review and evaluate the impact of this Act and the amendments made by this Act” and to issue findings and recommendations on (among other things) the “impact of immigration…on labor needs, employment, and other economic and domestic conditions in the United States.” That commission became known as the “Jordan Commission,” after its chairwoman.

Jordan’s commission worked for six years, during which Jordan herself offered multiple testimonies. Their recommendations to create a “credible, coherent immigrant and immigration policy” and a “credible, efficient naturalization process” included setting an immigration admissions level of 550,000 per year, to be divided as follows:

We can never know for sure, but Congress likely would have passed her recommendations had Jordan lived. President Clinton endorsed Jordan’s vision before she died. Without her unimpeachable credibility leading the effort, however, Jordan’s recommendations were either watered down in the final bill or cut entirely. David Leonhardt writes in Ours Was the Shining Future:

“By the 1990s, a powerful, bipartisan coalition had come to support the status quo on immigration, and the recommendations of Jordan’s commission quickly came under attack. Business lobbyists and Republican leaders in Congress favored high immigration partly because it restrained wage growth. They also worried that reducing immigration would keep out future entrepreneurs. Liberal groups saw immigration as a human rights and civil rights issue and pointed out that any reductions would mostly effect Latin American and Asian immigrants, given that those regions accounted for most immigration. Many of Clinton’s aides were also dubious of any policy that seemed to be trying to slow down globalization. It was part of his administration’s neoliberal instincts.

“By the summer of 1996, Clinton had quietly backed away from Jordan’s recommendations. Congress instead passed several provisions to reduce illegal immigration, though they were less aggressive than the commission’s proposals. The laws governing legal immigration remained largely the same.”

Jordan’s relevance today

NumbersUSA was founded the year Barbara Jordan died. From day one, we have advocated for her commission’s recommendations. Her work in the last years of her life – in the last act of public service to her country – is at the core of our work. We have unfinished business. There is work left to do.

Jordan’s diagnosis of our immigration ailments is as applicable today as it was in her lifetime. Millions of Americans still do not have adequate job prospects. We are still not providing adequate protection to vulnerable workers. America still lacks credible enforcement in the workplace, interior, and at the border.

Moreover, Jordan’s vision remains the standard for aligning the pro-worker approach of 1924 to the anti-discriminatory approach of 1965. How many? Which ones? Jordan didn’t just have the right answers, she asked the right questions. Celebrate her birthday today and honor her legacy by taking some action to achieve her vision of a sensible immigration policy. Jordan believed in the national community. She believed in Democracy. When we act together, using the tools of Democracy, we provide yet one more piece of evidence that “the American dream need not forever be deferred.”

Barbara Charline Jordan (February 21, 1936 – January 17, 1996)

Listen: Who Was Barbara Jordan and Why Does Her Work Still Matter Today? Parsing Immigration Policy, with Mark Krikorian, Executive Director of the Center for Immigration Studies, and Eric Ruark, Director of Research at NumbersUSA.

Take Action

Your voice counts! Let your Member of Congress know where you stand on immigration issues through the Action Board. Not a NumbersUSA member? Sign up here to get started.

Donate Today!

NumbersUSA is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that relies on your donations to works toward sensible immigration policies. NumbersUSA Education & Research Foundation is recognized by America's Best Charities as one of the top 3% of well-run charities.

Immigration Grade Cards

NumbersUSA provides the only comprehensive immigration grade cards. See how your member of Congress’ rates and find grades going back to the 104th Congress (1995-97).